While baseball has storied Cooperstown, N.Y., as its birthplace, softball’s creation began at Minneapolis Fire Station No. 19 — now a Buffalo Wild Wings on University Avenue SE. near Williams Arena.

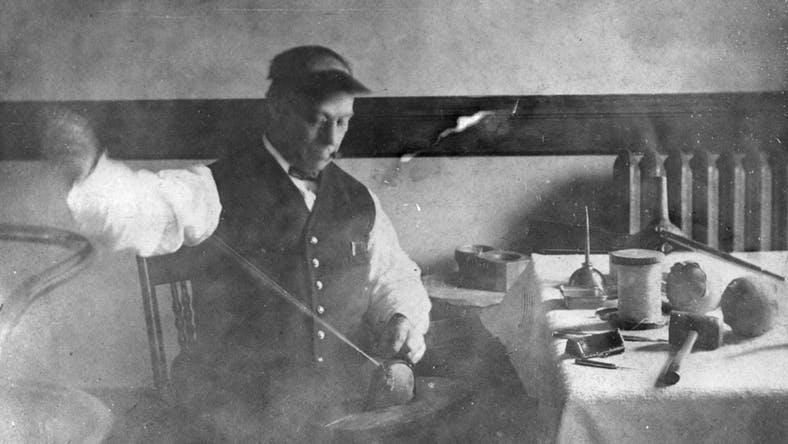

A lieutenant with the Minneapolis Fire Department, Lewis Rober was pushing 40 and perhaps getting a little flabby. So in 1895, he devised a sporting alternative to keep himself and his fellow firefighters fit between runs.

Rober is widely considered the founding father of softball — at least the outdoor version of the game now enjoyed by 40 million people. He took the basics of baseball, shrank the field and used a cushy ball pitched underhand. With no gloves needed and less time required, the recreational version of baseball took off.

“Using a vacant lot adjacent to the firehouse, Rober laid out bases with a pitching distance of 35 feet,” according to the website of USA Softball, the sport’s national governing body in Oklahoma (tinyurl.com/Mpls-softball). “His ball was a small sized medicine ball with the bat two inches in diameter. The game became popular overnight and other fire companies began to play.”

Rober named his first team the Kittens, so his game became known as Kitten Ball until the Minneapolis Park Board re-christened it Diamond Ball in the early 1920s. Also called “pumpkin ball” and “mush ball,” the sport wasn’t known as softball until 1926.

While baseball has storied Cooperstown, N.Y., as its birthplace, softball’s creation began at Minneapolis Fire Station No. 19 — now a Buffalo Wild Wings on University Avenue SE. near Williams Arena.

“Fire Station No. 19 is historically significant as the birthplace of a major variant of American softball known as ‘kittenball,’ ” according to the 1982 nomination that landed the firehouse on the National Register of Historic Places.

Rober was at Fire Station No. 11 (2nd Street SE.) when he devised his game before being transferred to brick firehouse No. 19 from 1896-1906 — when he printed a rule book.

“The first of its kind ever published,” a 1906 story in the Minneapolis Tribune reported, the Kitten League Guide “will prove of great value to those playing this game.” The article said Rober “has been one of the strongest supporters of the game and through his efforts the sport has gained a strong foothold in Minneapolis.”

Census records show Rober was the second son of French Canadians, born in November 1855 in Baldwinsville, N.Y. — about 100 miles northwest of Cooperstown. By 1885, he had moved to Minneapolis, and the 1900 census listed him as a widowed firefighter and father of two.

Rober remarried and died in Hennepin County on Sept. 2, 1930, at 74 — eight years before his lofty status as softball’s Minnesota creator was called into question. A math teacher at Cretin High School, then in downtown St. Paul, rather sheepishly debunked Rober’s pioneering role in the game’s early years in Minnesota.

As if the Minneapolis-St. Paul rivalry didn’t have enough dickering, check out this March 20, 1938, headline in the Sunday Minneapolis Tribune:

“Kittenball’s Origin in Minneapolis? No! Says Teacher at Cretin Who Brought Game to Twin Cities From Chicago.”

Writer Louis Greene led his story thusly: “Prepare for a rude shock, all you thousands upon thousands of diamond ball players and devotees. For that story claiming a Minneapolis fireman originated the game — which the entire nation has believed — is now shaken to its foundations.”

The story explained how teacher Lawrence Sixtus “hurled the bombshell” and stated “unequivocally” that he played an indoor version of kitten ball in Chicago schools from 1892-1894. By 1898, the math teacher said he coached a uniformed team at Cretin which played indoor games against the St. Paul Athletic Club, National Guard teams and various all-stars.

Most softball historians agree the game started indoors at a Chicago boat club in November 1887. When alumni of Yale and Harvard learned the former had won their annual football game, a Yale graduate heaved an old boxing glove at a Harvard guy — who tried to hit it back with a stick. An indoor version of softball played in a gym sprung from that moment.

Softball historians widely credit Rober with moving the game outdoors. There’s scant mention of the contributions of Cretin’s Sixtus, who was well aware of Rober’s standing as softball’s inventor in 1895.

Being a good Catholic, “Brother Lawrence has refrained from pushing himself to the fore in undignified denial,” the 1938 story said. “Even when pressed he refused to cast any aspersions on the claims to authorship on Rober’s behalf.” He “merely insisted” playing indoor softball in Chicago before 1895 and coaching a team at Cretin.

By the time Rober came out with his rule book in 1906, Brother Lawrence said 17-inch-circumference softballs were readily for sale in Chicago along with softball bats. Rober’s version of the rules called for balls 12 inches in circumference. That’s closer to the size commonly used today, although 16-inch softball remains popular in Chicago.

Whoever deserves the credit — the fireman or the math teacher — by 1936, in the midst of the Depression, nearly a half-million people were watching 10,000 players compete on 151 diamonds in Minneapolis alone.

“Diamond ball is not baseball,” Minneapolis Park Board recreation director Karl Raymond said in 1936. “It finds its basis in baseball, but it does not require the high degree of organization, nor the complete equipment that baseball requires. It is essentially a game of recreation.”

And for that, we can thank a Minneapolis fireman trying to stay fit — or a math teacher in St. Paul. Take your pick.

Softball born here

Minneapolis firefighter Lewis Rober, a pipeman on a chemical rig, is considered the father of outdoor softball — a game he devised to keep firemen fit in 1895.

Here’s a quote from Minneapolis assistant fire marshal George Wilson, looking back in 1936:

“Things were different in those days. There was a lot of vacant space around fire stations and it was no trick at all to lay out a diamond. The game itself did not require a great deal of space so the men could get plenty of exercise and enjoyment. ”

Minneapolis Park Board recreation director Karl Raymond said, in 1936, a smaller field paved the way for the sport’s popularity among women: “The longer baseline [in traditional baseball] makes the game too difficult, especially for girls, and also requires a larger area for play,” Raymond said. “Using the shorter distances, the game is much more adaptable for athletic recreation.”